Hydrogen is the simplest and most abundant element in the universe(1). It is a basic building block in star formation(2) and ever-present in water, organic molecules and the Earth’s atmosphere. The gas is highly flammable and burns together with oxygen to form water. This key property explains the element’s name: the term hydrogen is derived from the Greek words for ‘creator’ and ‘water‘. The first scientific encounter with hydrogen took place in the late 16th century. However, the gas was confused with other flammable gases. Finally, in 1766 the chemist and physicist Henry Cavendish recognised hydrogen gas as an independent substance. He named it ‘flammable air’. Nowadays, hydrogen is widely used in the chemical industry, for example in the production of ammonia(1). Hydrogen is used as a low carbon fuel, particularly for heat; but also for hydrogen vehicles, seasonal energy storage and long distance transport of energy(4).

Researchers at Radboud University have discovered microorganisms that can live on the energy of hydrogen gas. As Prof. dr. Huub op den Camp explains: “These 'Knallgas' microbes only need hydrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide and some minerals to grow. In addition, they are so efficient that they can even absorb atmospheric concentrations of hydrogen (0.53 ppm)”.

This group of hydrogenase (enzymes that catalyse the oxidation of H2) could be a strong controlling factor in the global H2 cycle1. The methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV, isolated from a volcanic mud pot, is thus far the only known methanotroph organism that can also rapidly grow on H2 as sole energy source, as well as oxidize subatmospheric H2(5). This not only implies the positive contribution these organisms can have in global warming (as methane-eating organisms), but also opens up a whole range of possibilities in creating a truly circular hydrogen economy.

Research on methane- and methanol eating bacteria, specifically methanol dehydrogenase, plays an important role in the Master’s course Genomics of Health and Envrironment, a collaboration between the departments of Molecular Biology, Human Genetics and Microbiology. Several Master’s internships provide opportunities to join this research, or co-author important scientific articles.

Sources

(1) hydrogen | Properties, Uses, & Facts. (2020, 1 June). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/hydrogen

(2) What’s in the Milky Way? (2019, 1 February). Curious. https://www.science.org.au/curious/space-time/whats-milky-way

(3) Wikipedia contributors. (2020a,24 July). Hydrogen. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydrogen

(4) Wikipedia contributors. (2020, 25 August). Hydrogen economy. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hydrogen_economy

(5) Schmitz, R. A., Pol, A., Mohammadi, S. S., Hogendoorn, C., van Gelder, A. H., Jetten, M. S. M., Daumann, L. J., & Op den Camp, H. J. M. (2020). The thermoacidophilic methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum SolV oxidizes subatmospheric H2 with a high-affinity, membrane-associated [NiFe] hydrogenase. The ISME Journal, 14(5), 1223–1232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-020-0609-3

Helium is the smallest of all elements: its electrons are in a tight orbit due to the highly charged core(1). Helium is an inert, non-reactive, colourless gas and the second most abundant element in the universe. Helium molecules are mostly found in natural gas fields. It is the lightest noble gas, and widely known as a balloon filling. Because helium has the lowest melting and boiling point of all elements, it is an especially suitable coolant for many applications that require extremely low temperatures, such as superconducting magnets (e.g. in NMR and MRI equipment), cryogenic research and nuclear reactors(2). However, helium is becoming increasingly scarce, as the demand for natural gas (LNG) is declining.

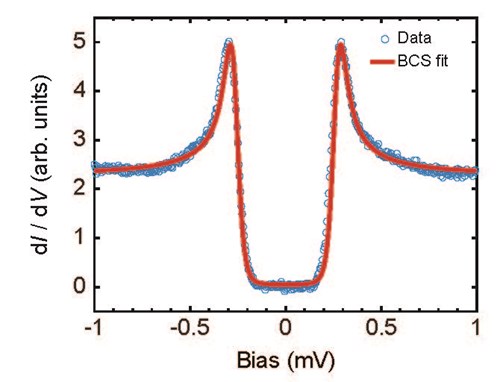

Helium is used in research at the HFML-FELIX at Radboud University. Sanne Kristensen, PhD student Physics, examines fundamental properties of materials, especially the behaviour of electrons in materials under the influence of a strong magnetic field. “Unfortunately, the temperature of the environment around the research setup disturbs our measurements, since temperature also has a great effect on the electrons in a material. It is therefore often not possible to see the effect of a magnetic field on electrons at room temperature. Therefore, we need to cool our materials as close to absolute zero as possible, -273.15 degrees Celsius. We do this with liquid helium, which is 4 degrees above absolute zero. By playing with pressure differences of the helium and using the isotope helium-3, we manage to cool down our measurements to 0.05 degrees above absolute zero. At this low temperature, almost all temperature interference has been filtered out and we can see new effects in the materials we are researching. With this research we hope to better understand how effects such as superconductivity, quantum fluctuations and magnetism work”.

Sources

(1) Periodiek systeem - informatie over alle elementen - VNCI. Periodiek Systeem. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://periodieksysteem.com/element/helium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020, August 7). Helium. Wikipedia. https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helium

Lithium is the lightest solid element and the metal can even be cut with a knife. However, chances are slim you will ever do this as it does not appear as a metal in nature. In its free state, it is highly reactive and flammable. Usually, it is found in oceans, mineral compounds, and brine. The latter is the main resource in the large-scale industrial production of lithium. This production skyrocketed during the Cold War because lithium is a useful resource for nuclear weapons(1). Nowadays, its purposes are more wholesome. Lithium is often used in heat-resistant ceramics and for lithium-ion batteries. In fact, the 2019 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to three scientists who developed lithium-ion batteries, which have revolutionized portable electronics(3). Although these batteries are expensive, they can last for decades. This makes them a popular power supply in pacemakers and watches. Also, lithium salts are known mood stabilizers: they can offer a valuable treatment of bipolar disorders(2).

Researchers at Radboud University are studying Lithium-ion batteries. Prof. Arno Kentgens at the Magnetic Resonance Research Center: "Lithium-ion batteries are currently used in most portable devices, such as mobile phones and laptops, because of their high energy per unit mass, compared to other electric energy storage methods. They also have a high power to weight ratio, a high energy conversion efficiency, perform well under high temperatures and have little self-discharge. This is why the current generation of electric cars also has lithium-ion batteries. However, these still have some shortcomings: the weight and price of an electric car is based for over 30% by the batteries, and there are safety risks."

"For a battery with a high energy density, it would be preferred to use a lithium-metal anode, but there is a problem: so-called dendrites will grow between the anode and the cathode, cause the battery to short-circuit. These dendrites easily frow through the separator between the electrodes, which consists of a fluid electrolyte. The fluid electrolytes are highly inflammable and a short circuit could even lead to exploding batteries. This had led to worldwide research on solid electrolytes, which should let lithium-ions pass through easily but do not conduct electrons. Especially the surfaces between the cathode, anode, and the solid play a crucial role. The anode, electrolyte and cathode must react to each other, which is why a protective film is needed, called the ‘solid electrolyte interphase’. It has to be extremely stable and conduct lithium-ions well. NMR is especially a good method to study in detail how lithium moves through the different battery materials and how the structure of a material influences the conductivity of lithium. This is why researchers of Radboud do a lot of research on this, together with colleagues from the Netherlands and abroad."

Sources:

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Lithium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 24, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lithium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). lithium | Definition, Properties, Use, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/lithium-chemical-element

(3) Sheikh, K. (2019, October 10). Lithium-Ion Batteries Work Earns Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 3 Scientists. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/09/science/nobel-prize-chemistry.html?searchResultPosition=4

Beryllium and the corresponding salts have a sweet taste, as was discovered by old-style chemists who thought tasting chemicals was a worthwhile research method. This taste led to the element’s former name Glucine, based on the Greek ‘γλυκύς’ (sweet) that is also found in the word ‘glucose’. Nowadays, it is known that beryllium is highly toxic – and chemists are no longer prone to eat their substances(1). Being exposed to beryllium, for example via dust in the air, can cause a chronic and life-threatening disease called berylliosis. Hence, elaborate control equipment is crucial in any application of beryllium. This was overlooked during World War II, when the demand for fluorescent lights containing beryllium alloys rose. A survey later found that 5 percent of the workers in such manufacturing plants had lung diseases related to beryllium(2). Despite its toxicity, beryllium still has multiple applications due to its unique qualities. For instance, it is one of the lightest metals and it has one of the highest melting points among the light metals, namely an astonishing 1287 degrees Celsius(3). Its lightness and stability over a wide temperature range make it popular in high-speed aircraft, guided missiles, and satellites, including the James Webb telescope. Also, beryllium played a central role in an experiment carried out in 1932 by James Chadwick, which would earn him the Nobel Prize in Physics. He bombarded a sample of beryllium with radium alpha rays and consequently discovered the neutron(2)!

Sources

(1) Beryllium Element Facts. (2012, October 9). Chemicool. https://www.chemicool.com/elements/beryllium.html

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020, July 25). Beryllium. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beryllium

(3) Live Science. (2017, October 7). Facts About Beryllium. https://www.livescience.com/28641-beryllium.html

Compounds of boron, specifically borax, have been known since ancient times. Boron is produced entirely by cosmic ray spallation – formation of chemical elements from the impact of cosmic rays(1) – and supernovae and is thus a low-abundance element in the solar system and Earth’s crust. Boron was recognized as an element in 1808, when Louis-Josef Gay-Lussac and Louis-Jacques Thénard working in Paris, and Sir Humphry Davy in London, independently extracted boron(3).

Traces of boron are needed for the growth of many land plants and thus indirectly essential for animal life(2). When soil is abundant in boron, plant species can exhibit ‘gigantism’, as boron is important for the growing tips of plant shoots. Boron compounds are being researched and applied in a wide spectrum of biomedical applications. Some are studied as a potential treatment for tumours in the body, so-called boron neutron capture therapy. Upon injection, boron compounds will accumulate in the tumour. Every time a boron nucleus captures a neutron, transmitted by radiation therapy, a tissue-damaging alpha particle is released, which destroys the tumour tissue without affecting the healthy tissue around it(2). The expulsion of such a high energy alpha particle, makes boron isotopes also useful in the nuclear industry, as neutron shields or control rods in nuclear reactors(3).

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 7). Cosmic ray spallation. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmic_ray_spallation

(2) boron | Properties, Uses, & Facts. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/boron-chemical-element

(3) Boron - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/5/boron

Without carbon, there would be no life – or at least; not as we know it. Carbon is one of the few elements known since prehistoric antiquity. Carbon serves as a common element of all known life, because it is so abundant, diverse, and able to form polymers at temperatures commonly encountered on Earth(1). The atoms of carbon can bond together in various ways, resulting in different allotropes of carbon. The best known allotropes are graphite, diamond and ‘buckyball’. This last one refers to Buckminsterfullerene; a fused-ring structure resembling a soccer ball (image), made up of molecules of 60 (or 70) carbon atoms. The molecule has been detected in deep space in the interstellar medium spaces between the stars(3).

One recent discovery within the carbon-realm is graphene; an elusive two-dimensional form of carbon(2). Graphene is more than 200 times stronger than steel, an excellent thermal and electrical conductor, flexible, very thin and transparent; which makes it potentially suitable for a wide range of applications. Graphene was discovered by researches in the High Field Magnet Laboratory (HFML) at Radboud University. The 2010 Noble Prize in Physics was awarded to Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, both professors at our Faculty of Science.

As the common element of organic molecules in all known life, carbon is one of the most studied elements in chemistry, as chemical reactions are largely aimed at making or breaking C-C bonds.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Carbon. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon

(2) Meer, B. (March 19, 2018). Bekijk: Grafeen. NEMOKennislink. https://www.nemokennislink.nl/publicaties/grafeen/

(3) Wikipedia contributors. (August 20, 2020). Buckminsterfullerene. Wikipedia. Retrieved August 20, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buckminsterfullerene

The fixation of inorganic carbon (CO2) in organic carbon (carbohydrates, proteins, fats) starts with the primary producers (including plants and algae) who convert CO¬2 into glucose (C6H12O6) with the help of light and water. Other species eat the primary producers, creating a food web in which organic carbon is transferred from one organism to another. When organic carbon is used as an energy source, the stored carbon is released again with the help of oxygen in the form of CO2, which completes the circle.

In some ecosystems, such as in bogs, the organic carbon is not completely broken down due to a lack of oxygen in the soil. Here the organic material accumulates in several meters thick packages. When this is covered by sediment and stored in the soil for millions of years, it creates petroleum, natural gas, coal and lignite, or the fossil fuels that we have been using intensively since the 18th century. When it is combusted, the greenhouse gas CO2 is released into the atmosphere, which was no longer present in our biosphere for millions of years, causing an imbalance and warming up our climate. Current peat areas where a lot of carbon is stored have also been drained en masse, releasing the captured CO2 and contributing to global warming.

The big scientific question that this poses for ecologists is: How can we restore ecosystems such as wetlands and bogs so that the balance in biodiversity and carbon exchange is improved? Another question is what the impact of the changing climate is on ecosystems and how sensitive systems are to changes.

Nitrogen was discovered by Daniel Rutherford in 1772. He called it noxious air, because it can extinguish a flame(1). Nitrogen is a common element in the universe. At standard temperature and pressure, two atoms of the element bind to form dinitrogen (N2). Dinitrogen forms about 78% of Earth's atmosphere, making it the most abundant uncombined element. Nitrogen is extremely important to (the origin of) life, as it is an essential component in amino acids, proteins, DNA, and the energy-carrying molecule adenosine triphosphate(1).

Nitrogen is an important component of molecules in every major drug class in pharmacology and medicine, from antibiotics to neurotransmitters and beyond. One important aspect of nitrogen is that it is the only non-metal that can maintain a positive charge at physiological pH(3).

Nitrogen has been in the news a lot in recent years in the "nitrogen crisis". Because the amount of reactive nitrogen on Earth (due to agriculture, fossil fuels, traffic, shipping, etc.) has doubled in the past century, we now have a nitrogen surplus(2). Since nitrogen normally occurs in scarcity, many plants and animals have learned to use it very efficiently and are now overconsuming this previously valuable substance. The plants that grow the fastest, such as nettles, grasses and brambles, overgrow slow growers, which affects insects and birds. In addition, nitrogen acidifies the soil, causing important substances such as calcium to wash away from the soil. The negative effects of a nitrogen surplus are not only visible on land: via rivers, it flushes to the sea, where the nutrient-rich substance causes excessive algae growth that suffocates fish off our coast. It then evaporates and ends up in the air as nitrous oxide, a gas that is an enormous contributor to global warming.

Evan Spruijt, assistant professor Physical Organic Chemistry at Radboud University, tells you more about Nitrogen in the video below.

Click on "Read more" for information about Nitrogen in research at Radboud University.

Microbiology researchers at Radboud University are working with anammox bacteria; essential bacteria for nature and industry, because they can convert noxious nitrogen (in the form of ammonium NH4+) into a harmless variant, namely nitrogen gas (N2). The research on anammox is one of the main projects of the RU Microbiology group and was recently awarded an ERC Advanced grant. With the discovery of anammox bacteria, a missing link was found in the nitrogen cycle. Because of this favourable conversion from which the bacteria get their energy, anammox bacteria are already used in wastewater treatment.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2001, March 23). Nitrogen. Wikipedia. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nitrogen

(2) van Dongen, A., & Voermans, T. (2019, 21 september). Waarom liggen bouwprojecten stil? En 13 andere vragen over stikstof. AD. Retrieved August 1, 2020, from https://www.ad.nl/binnenland/waarom-liggen-bouwprojecten-stil-en-13-andere-vragen-over-stikstof~ad4491d5/

(3) Nitrogen and Phosphorus | Boundless Chemistry. (n.d.). Lumen Learning. Retrieved September 1, 2020, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-chemistry/chapter/nitrogen-and-phosphorus/

Oxygen was discovered in 1771 by the Swedish pharmacist Karl Wilhelm Scheele. Later, experiments of the British chemist Joseph Priestley made the gas more widely known(1). It was soon understood that this gas, although only making up one-fifth of the planet's air, allows combustion, as well as the breathing of humans and animals. Oxygen gas is indispensable for many organisms on Earth; without it, there would be no aerobic dissimilation – combustion of organic molecules to generate energy – possible. Oxygen atoms are important components of carbohydrates, which provide energy to living organisms.

In recent years there have been concerns about oxygen levels in the sea, which is declining at an unprecedented rate. Due to global warming and intensive agriculture, oxygen is slowly disappearing from the sea(2). In the past fifty years, the number of so-called ‘dead zones’, where there is no oxygen in the water, has quadrupled. In the dead zones, the oxygen level is so low that most marine animals cannot survive. Fish avoid the spots and have to retreat to smaller habitats.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). lithium | Definition, Properties, Use, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/lithium-chemical-element

(2) Wetenschappers slaan alarm op klimaattop Madrid: ‘Zuurstof in zee neemt razendsnel af’. (2020, December 7). AD. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.ad.nl/buitenland/wetenschappers-slaan-alarm-op-klimaattop-madrid-zuurstof-in-zee-neemt-razendsnel-af~a3ef133f/

Fluorine is a pale, yellow gas at room temperature. Since the electron configuration of fluorine lacks only one electron to form the stable noble gas neon, the fluorine atom attracts electrons very strongly. Fluorine is therefore by far the most aggressive oxidiser known among the elements and affects almost everything; even materials such as glass or asbestos burn in fluorine gas at room temperature. Because fluorine as a pure gas is such a reactive element, it does not exist naturally in its pure form(1). Salts of fluorine (fluorides) can be found in the Earth's crust, in rocks, coal and clay. Fluorides are released into the air by means of wind blown soil. Small amounts of fluorine naturally occur in water, air, plants and animals(2). Because of this, people come into contact with fluorine through food, drinking water and breathing air. Fluorine can be found in relatively small amounts in all types of food. It is essential for maintaining the strength of the bone system and preventing tooth decay, which is why it is added to toothpaste.

Sources

(1) Fluor. (2012, September 22). Visionair. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.visionair.nl/wetenschap/het-periodiek-systeem-fluor-f/

(2) Fluor (F). (n.d.). Lenntech. Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.lenntech.nl/periodiek/elementen/f.htm

Neon is a very common element in the universe and solar system (it is fifth in cosmic abundance after hydrogen, helium, oxygen and carbon), but it is very rare on Earth. The reason for this is that neon vaporises quickly and thus forms no compounds to fix it to solids. As a result, it easily escapes the Earth’s atmosphere under the warmth of the sun(2). Neon was discovered in 1898 by the British chemists Sir William Ramsay and Morris W. Travers in London(1). They immediately noted the characteristic red-orange color emitted under spectroscopic discharge. Neon’s distinct glow is still used abundantly in (advertising) lighting(2). Neon is also often used as a heat transport medium in cooling installations.

Neon played an important role in research into the origins of our planet. Previously, researchers were unsure whether the planet formed relatively quickly from a cloud of gas and dust around the sun, or if it took long time, with gases and water brought in later by meteorites. Research into neon in the Earth’s mantle has shown that it must have been the first scenario; the Earth was formed relatively quickly, within a few million years, from the cloud of gas and dust in which the young sun was then still enveloped(3).

Click on the button below to read about neon's use in research at the FELIX Laboratory at Radboud University.

Sources

(1) Neon (Ne). (n.d.). Lenntech. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.lenntech.nl/periodiek/elementen/ne.htm

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020, April 16). Neon. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neon

(3) E.E. (n.d.). Neon uit aardmantel wijst op snelle vorming van de aarde. Zenit. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://zenitonline.nl/neon-uit-aardmantel-wijst-op-snelle-vorming-van-de-aarde/

Neon is used in research at Radboud University at the FELIX Laboratory (Free Electron Lasers for Infrared Experiments). “In our lab, we are mainly interested in the structure and reactivity of molecular ions.”, says Daniel Rap, PhD student at FELIX. “Infrared spectroscopy can be used to study the vibrations of molecules in order to determine the 3D structure of the molecule. However, when studying ions, the traditional way of infrared spectroscopy (that is, measuring absorption of the irradiated light) does not work because we are talking about a few (ten) thousand ions that we want to study. There is then too little difference between the incoming and outgoing light to measure. This is where neon comes into play. Under cold conditions (6 Kelvin; -267 °C), we can connect the molecular ion and the neon atom with a very weak bond. In this way, neon functions as a 'tag', as it were: when we use the infrared laser, the energy of the light causes the neon atom, which is very weakly bound, to become detached from the ion. In this way we can count how many of the ion / neon complexes we have at which wavelength of the infrared light. And this gives us the possibility to measure an infrared spectrum of a few thousand ion / neon complexes and thus determine the structure of the ion.”

Sodium is an essential element for life. As part of salts, it is found in almost any biological material(1). Its importance in your own body should not be taken with a grain of salt either. For example, it regulates blood pressure and osmotic processes. For a less abstract image, picture that sodium is one of two building blocks in common salt (NaCl). The element’s name comes from the Latin word ‘sodanum’. This was a compound containing sodium, used for headache relieve in Medieval Europe. In the present day, sodium is used to produce soap, glass, paper, textiles, synthetic rubber, pharmaceuticals, and so on. In other words, it is of immense commercial importance. However, do not think that sodium metal is easy to handle. It is extremely reactive – generally more so than lithium – and hence does not occur freely in nature. In fact, pure sodium powder may explode when it touches even the slightest amount of water, like the moisture on your hand(2).

Sources:

(1) sodium | Facts, Uses, & Properties. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 27, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/sodium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Sodium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sodium

Without magnesium, life as we know it would not exist. It lies at the core of chlorophyll, which in turn lies at the core of photosynthesis in plants, which in turn lies at the core of the food chain. Hence it is essential to all plant and animal life, including your own body, where it is indispensable for hundreds of enzymes. For example, “your nervous system could not function without it, because it is important for nerve impulse conduction”, explains Sharon Kolk, associate professor in Neurobiology at Radboud University. “It also supports memory and learning.” Luckily, deficiencies are rare because human skeletons carry sufficient storage. Otherwise you could eat some magnesium-rich food like almonds, soybeans, cashew nuts and chocolate(1). However, magnesium also has a history of not creating but destroying life. Although it is hard to ignite in bulk, its fires are very hard to extinguish as water only stimulates the combustion. This property was exploited during firebombing of cities during World War II, where civilians could only try to smother fire with dry sand(2). The brilliant light it produces when ignited is also used for more friendly applications like photography, flares and pyrotechnics(3). It is also used when products can benefit from being lightweight, such as laptops and race bikes (a steel frame can be nearly five times as heavy as a magnesium one). People have also been using magnesium compounds as laxatives for centuries(1).

Sources

(1) Magnesium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). www.rsc.org. Retrieved August 3, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/12/magnesium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Magnesium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnesium

(3) Magnesium Element Facts. (2012, September 13). www.chemicool.com. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from https://www.chemicool.com/elements/magnesium.html

Compounds of aluminium have been known since ancient times. Only in the beginning of the 19th century researchers managed to extract aluminium in its pure form. For a long time after this, aluminium was so valuable that it was mainly used in decorative or luxurious ornaments. In pure form aluminium is soft and not strong. But in alloys with small amounts of copper, magnesium, silicon, manganese or other metals, it is suitable for all kinds of applications. Aluminium is the most common metal on Earth, but it does not exist in its pure form. It takes a lot of energy to isolate it from ore (bauxite). For a long time it was more expensive than gold, until technology was developed in the 19th century for large-scale aluminium production(1). The metal has been available for a little over a century now, and during that time it has stormed the world. Aluminium is light, durable and resistant to corrosion. It is a good conductor, it does not spark, and it forms relatively easily(2). Aluminium is therefore not only applicable in many consumer products - such as packaging material, toys, household equipment (pans, cutlery), camping equipment (folding chair, tent poles), furniture or even food colouring - it also plays an important role in more industrial applications, such as the automotive industry, power lines, lightning rods, antennas, and the light and sound industry.

Sources

(1) Periodiek systeem - informatie over alle elementen - VNCI. (z.d.). Periodieksysteem. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://periodieksysteem.com/element/aluminium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Aluminium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aluminium

Silicon makes up 27.7% of the Earth’s crust by mass and is the second most abundant element on the planet, after oxygen. Silicon is one of the most useful elements to mankind(1): it is the principal component of glass, cement, concrete, steel, bricks, most semiconductor devices, and silicones(2). The element silicon is used extensively as a semiconductor in solid-state devices in the computer and microelectronics industries. That is why the high-tech region of Silicon Valley in California is named after silicon(3), and the late 20th century to early 21st century period has even been described as the Silicon Age, due to the element’s large impact on the modern world economy.

Sources

(1) Silicon - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/14/silicon

(2) Silicon (Si) - Chemical properties, Health and Environmental effects. (z.d.). Lenntech. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.lenntech.com/periodic/elements/si.htm

(3) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Silicium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Silicium

Phosphorus was discovered in 1669 after an unusually filthy experiment: Hennig Brand, a German physician and alchemist, boiled, filtered and processed as many as 60 buckets of urine to isolate the element phosphorus(1). Brand called the substance he had discovered ‘cold fire’ because it was luminous, glowing in the dark(2). Phosphorus has three main allotropes: white, red, and black.

One of the most abundant usages of phosphorus is as a fertiliser: in the process of converting phosphate rock to usable materials, calcium hydrogen phosphates are formed, which are important to make fertiliser or food supplements for animals(3). Besides its use in fertilisers, elemental phosphorus applications include fireworks and matches, because it allows combustion at the temperature of frictional heat(4).

Concerns have arisen about phosphorus use, however. On its journey from mining to consuming (by animals, but also indirectly; humans), most of the phosphorus is wasted and ends up in waterways where it can cause algal blooms.

Phosphorus (P) is an essential element in biology, and mainly occurs in the environment as PO4. This is an essential nutrient for organisms and an important component of DNA, RNA, ATP and phospholipids.

The ratio of phosphorus compared to other elements (like carbon and nitrogen) in organisms is a property that is used to indicate the degree of which an organism is a nutritional resource for grazing animals and predators.

Many ecosystems, such as lakes and grasslands, have limited phosphorus. An increase of phosphorus, for example via a fertiliser, can lead to an explosive growth of plants in the ecosystem. The department of Aquatic Ecology & Environmental Biology conducts research on the ecological restoration of ecosystems that have a lot of phosphorus due to fertilisation in the past. This can be done by digging up the soil with a lot of phosphorus or by growing plants that easily take up phosphorus from the environment, such as Azolla.

In lakes, an abundance of phosphorus can make a clear ecosystem with submerged plants turn into a troubled state with (poisonous) algae. Next to the shift in species, this turn can influence other ecosystemic processes, such as methane production in the sediment.

Sources

(1) Gagnon, S. (n.d.). It’s Elemental - The Element Phosphorus. JLab Science Education. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele015.html

(2) Stewart, D. (2012, September 28). Phosphorus Element Facts. Chemicool. https://www.chemicool.com/elements/phosphorus.html

(3) Gregersen, E. (z.d.). phosphorus | Definition, Uses, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/phosphorus-chemical-element

(4) Cunningham, J. M. (n.d.). Match. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/match-tinder#ref15123

Sulfur is the fifth most common element on Earth and has been known and used since ancient times. It is mentioned – sometimes referred to as brimstone, ‘burning stone’ – in ancient India, Greece, China and Egypt. Elemental sulfur is mostly found near hot springs and volcanic regions, perhaps explaining why in the Bible sulfur or brimstone is often associated with hell and fury(1).

The majority of the sulfur produced today comes from underground deposits through a process known as the Frasch process(2). Today, its most common use is in the manufacture of sulfuric acid, which is used in fertilisers, batteries and cleaners. It is also used to refine oil and in processing ores(1). Many sulfur compounds are odorous and responsible for, among others, the smell of skunk, grapefruit, garlic, rotting eggs and other biological processes.

Volatile sulfur compounds are very malodorous and toxic, and are also produced in a number of industrial processes. Furthermore, they have a major impact on global warming and acid precipitation processes. Microbiology researchers at Radboud University are investigating the microbial degradation of volatile organic sulfur compounds. Studies of the degradation are coupled to the application of promising bacterial isolates in treatment of polluted air.

You can read more about this research at: ru.nl/microbiology/research

Sources

(1) Pappas, S. (2017b, September 29). Facts About Sulfur. Live Science. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://www.livescience.com/28939-sulfur.html

(2) Gagnon, S. (n.d.). It’s Elemental - The Element Sulfur. JLab Science Education. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://education.jlab.org/itselemental/ele016.html

At room temperature, chlorine is a yellow-green gas. It is an extremely reactive element and a strong oxidiser: among the elements, it has one of the highest electron affinities and the third-highest electronegativity. Chlorine is too reactive to occur in its native form in nature but is very abundant in the form of chloride salts. The most common chloride salt is sodium chloride (table salt) and has been known since ancient times. Archaeologists have found evidence that rock salt was used as early as 3000 BC and brine as early as 6000 BC(1).

The high oxidising potential of elemental chlorine led to the development of commercial bleaches and disinfectants. It is the most commonly used drinking water disinfectant in the world and protects millions of people against pathogenic microbes. It is also used as a reagent for many processes in the chemical industry.

Sources

(1) Weller, O., & Dumitroaia, G. (2005, December). Antiquity, Project Gallery: Weller & Dumitroaia. Antiquity. Retrieved July 16, 2020, from https://web.archive.org/web/20110430145935/http://antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/weller/

The name argon is derived from the Greek ἀργος, which means ‘lazy’ or ‘non-active’. A fitting name, considering that argon is colourless, odourless, non-flammable and nontoxic as a solid, liquid or gas. It is chemically inert under most conditions and does not form stable compounds at room temperature(1). Since the 18th century, chemists predicted that there would be a gas like argon in the air. But it was not until the late 19th century that Lord Rayleigh and William Ramsay experimentally proved that argon actually existed. The Earth’s atmosphere consists of 0,94% argon. It is now produced as an industrial gas; for example as filler in light bulbs – argon prevents the filament from burning at high temperatures – or as blue light- because like neon, it emits a bright colour under spectroscopic discharge. Because of its inert characteristic, it is also used as protection in processes like welding, titanium production, or the development of crystals(2).

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2020d, July 9). Argon. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Argon

(2) Lenntech. (n.d.). Argon (Ar). Lenntech. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.lenntech.nl/periodiek/elementen/ar.htm

The name potassium is derived of the Dutch word “potas” (pot ash), because potassium carbonate was originally obtained by leaching wood and then heating the substance to 'ash' in a pot(1). Ironically, in Dutch and other Germanic languages the word for potassium (‘kalium’) comes from the Arabic “al-qalyah” (meaning ‘ash from plants’), whereas almost all other languages use the Dutch derivative. In the 19th century, it was discovered that potassium salts are also extractable from mines. This put an end to virtually all extraction of potash from wood in Western Europe and North America(3).

As an alkali metal, potassium has a single outer shell electron, that is easily removed to create an ion with a positive charge (cation). Because of this positive charge, the potassium ion easily combines with ions that have a negative charge (anions) forming a salt. Therefore, potassium in nature occurs only in salts(2). Potassium ions are vital for the functioning of all living cells; it is necessary for normal nerve transmission. Fresh fruits and vegetables are good dietary sources of potassium.

Potassium has been used at Radboud University in research by the Scanning Probe Microscopy department (SPM). The scanning tunneling microscope is a measuring instrument at the Institute for Molecules and Materials, used to examine fundamental physics on the atomic scale.

Click on the button "Read more" to find out more about this research at Radboud University.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2020a, February 16). Kalium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020j, July 24). Potassium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potassium

(3) NutriNorm (2020, July 27) - Waar komt kalium vandaan. (n.d.). Nutrinorm. Retrieved July 20, 2020, from https://www.nutrinorm.nl/nl-nl/Paginas/Hoofdelementen-Waar-komt-kalium-vandaan.aspx#.Xx6ipkUzZPY

Potassium is an alkali metal and thus has one outer shell electron that is easily donated to its surroundings. This quality is useful in experiments involving doping. Research conducted at Radboud University concerned the structural arrangements of potassium atoms on the surface of black phosphorus. “The experiment was actually initiated accidentally”, Elze Knol, PhD student at Scanning Probe Microscopy, explains. “We were preparing a doping experiment with potassium atoms on black phosphorus, which is supposed to be kept under very cold circumstances (T < 5 K). One time, we forgot to add liquid helium to the STM, to keep the temperature down. The temperature started creeping up and after cooling back down, we noticed that the potassium atoms had moved and were now forming organized rows on the black phosphorus. That triggered our curiosity; what is happening here?”. In the experiment that followed, it was found that the potassium atoms were not distributed equally in all directions, but in the x-direction the atoms were much closer to each other than in the y-direction. This indicates that the black phosphorus screens the donated electrons from the potassium atoms in an anisotropic manner – unlike isotropic materials, which have identical physical properties in all directions.

Let’s put calcium in the limelight, literally. Lime is calcium oxide, which can be burnt with a special flame to create an intense light. This technique was used in the 19th century to light theatre stages, hence the expression. Nowadays we have light bulbs, but calcium still serves other purposes. For example, both humans and snails use it to build their houses, although only humans use it in cement. This building technique is age-old: the Romans used it in constructing aqueducts and amphitheatres(1) and lime was already used in buildings about 9000 years ago. It is no surprise that the element’s name is based on ‘calx’, the Latin word for lime. Of course, calcium also has many crucial biological functions. Sharon Kolk, associate professor in Neurobiology at Radboud University: “It is the most abundant metal in the human body and important in electrical signalling within the nervous system. It plays a key role in the release of neurotransmitters by neurons in the brain. This is very important for memory storage and retrieval. It is furthermore key to the maintenance of our blood pressure.” An average human body contains roughly 1 kg of calcium, of which 99% is stored in the bones. It can enter your body via foods like spinach, milk and almonds(2).

Sources

(1) Calcium Element Facts. (2012, October 4). Chemicool. Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://www.chemicool.com/elements/calcium.html

(2) Calcium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (z.d.). www.rsc.org. Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/20/calcium

Dmitri Mendeleyev already knew when he created his periodic table that there was an element missing that would be between calcium and titanium. He referred to it as ‘eka-boron’ because the element would be placed under boron in his table. Ten years later, in 1879, Swedish chemists stumbled upon the element, which was then named scandium because of its Scandinavian discoverers(1). Scandium is mostly used for research purposes(2). Global-scale, industrialized mining and production of scandium only really started in the 1970s, when its positive effects on aluminium alloys were discovered. This is still the most used application of scandium; used in LCD televisions, mobile phones, racing and mountain bikes. Scandium is almost as light as aluminium but it has a much higher melting point, which is now being researched for its usefulness in space exploration.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2018, November 25). Scandium. Wikipedia. Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scandium

(2) Scandium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved August 6, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/21/Scandium

Titanium is found abundantly on Earth, but due to its reactive nature, it is mostly bound to other elements in minerals and soils. It is also present in plants, animals and natural waters(1). Some meteorites and stars contain high concentrations of titanium. For example, rocks that Apollo 17 brought back from the Moon, consisted of 12.1% titanium dioxide(2). As a lightweight, high-strength, low-corrosion metal, titanium is used in alloy form for components in aircrafts, space crafts, missiles and ships. It also is used in prosthetic devices, because it does not react with fleshy tissue and bone(1).

“Titanium is an element used in a wide range of applications, either as a pure element or in specialized alloys. Being an excellent getter material, we use it to trap gas molecules that sporadic hit titanium covered chamber walls to maintain an ultra-high vacuum. Additionally, due to its two unpaired electrons in the atomic shell, it can exhibit interesting magnetic properties”, writes Manuel Steinbrecher, post-doc at Scanning Probe Microscopy.

“Within the experiments in our group, we have deposited single Ti atoms on an insulating magnesium oxide (MgO) surface. However, due to its aforementioned exceptional getter capabilities, we mostly observe the hydrogenated TiH molecule on the surface. Interestingly, TiH is one of the most abundant elements in outer space, but experimental data to confirm its electronic structure is still lacking. Using a ‘’scanning tunneling microscope’’ (STM) at ultra-low temperatures allows us to address and study individual TiH molecules. By irradiation with radiofrequency, we perform electron spin resonance (ESR) experiments, that relies on the same principle of magnetic resonance that MRI scans use for medical diagnostic With this technique and the help of cutting-edge quantum chemistry calculations, we have, e.g., studied the molecule’s conformational and electronic structure as well as its magnetic properties with a precision as never before. In the future, the ESR technique will enable us to examine different kinds of sample systems with a precision the standard STM technique cannot provide.”

Sources

(1) Augustyn, A. (n.d.). titanium | Properties, Uses, & Facts. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/titanium

(2) Periodic Table of Elements: Los Alamos National Laboratory. (n.d.). Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://periodic.lanl.gov/22.shtml

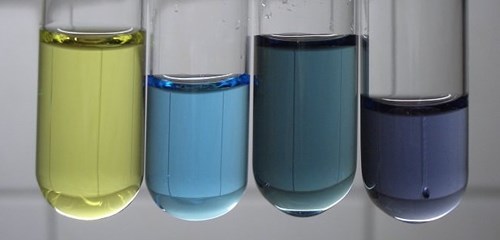

Vanadium was first discovered in 1801 by the Spanish-Mexican mineralogist Andrés Manuel del Rio. He named it panchromium, after the Greek ‘παγχρώμιο’, meaning 'all colours', because its salts had all kinds of different colours(1). But that name didn’t last long, because a French chemist erroneously convinced Del Rio he had not discovered a new element, but just a impure form of chromium. Thirty years later, Del Rio’s findings were proven right when a Swedish chemist ‘rediscovered’ the element. Since then, it was called vanadium, in honour of the Scandinavian goddess Vanadís, also a testament to its multicoloured compounds(2). Vanadium is a medium-hard, steel-blue metal. It is rare in nature in its native form, but compounds of vanadium are found naturally in minerals, mostly vanadite and carnotite. Most vanadium used today is processed in steel, making it stronger, lighter and stainless(3).

The chemistry of vanadium is noteworthy for its oxidation states. Vanadium can form compounds with water (solution for metal salts) of which the colours are lilac, green, blue and yellow-orange.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2019a, 11 February). Vanadium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vanadium

(2) Mindat. Vanadium: Mineral information, data and localities. (n.d.). Mindat. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.mindat.org/min-43604.html

(3) Blekemolen, J. (2020, 3 July). De beste vanadium aandelen van dit moment. Online Broker LYNX. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.lynx.nl/kennis/artikelen/beste-vanadium-aandelen-beleggen/

Chromium is a steely-grey, hard and brittle transition metal. It is the most important additive in stainless steel, mainly for its anti-corrosive properties(1). Chromium is also highly valued as a metal that can be highly polished without the common by-effect of corrosion. The name chromium is derived from the Greek word ‘chróma’, meaning colour, because many chromium compounds are coloured(2): the green colour of emerald, serpentine, chrome mica, and the red colour of ruby are due to small amounts of chromium(3). Chromium is the third hardest element behind carbon and boron. Because of its resistance to corrosive reagents, chromium is extensively used as an electroplated protective coating(3). For example, the compound chromium-6 has often been used in anticorrosion paint, but was recently proved to be harmful to humans. Chromium-6 is released when spraying with chrome-containing paint or by sanding, grinding, sawing or heating the painted surface. Dust that contains chromium-6 is then released into the air, which can cause cancer, among other things.

The element was discovered in 1797, but it would take until 1898 before pure chromium was extracted. By then ores and compounds of chromium were already extensively used, for example in leather tanning and steelmaking(4). Excavated swords and crossbow bolts found in burial pits suggests that chromium coating was even used as early as the third century BC(5).

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Chromium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chromium

(2) Haal de feiten over de Element Chromium. (2019, July 3). Greelane. Retrieved July 13, 2020, from https://www.greelane.com/nl/science-tech-math/wetenschap/chromium-element-facts-606519/

(3) Rafferty, J. P. (n.d.). Chromium | chemical element. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/chromium

(4) Bacon, F. E., & Downing, J. H. (n.d.). Chromium processing. Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/technology/chromium-processing

(5) Cotterell, Maurice. (2004). The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor's Army. Rochester: Bear and Company. ISBN 1-59143-033-X. Page 102.

Manganese is a hard, brittle, silvery metal. It is in fact so brittle, that it isn’t of much use as a pure metal. It is especially useful as an alloy, especially in stainless steels(1). Manganese is often found in minerals in combination with iron. It is also an essential element in all known living organisms, especially in many types of enzymes. For example, the enzyme used during photosynthesis contains atoms of manganese(2). Furthermore, manganese is key to normal cell function and metabolism.

Manganese is the fifth most abundant metal in the Earth’s crust. Its minerals are broadly scattered, pyrolusite (manganese dioxide) and rhodochrosite (manganese carbonate) being the most common. Pre-historic cave painters in France used pyrolusite (a black ore) as early as 30,000 years ago. In more recent times it was used by glass makers to remove the pale greenish tint of natural glass(2).

“Manganese is an essential metal that plays a fundamental role in brain development and functioning. Environmental exposure to it may lead to accumulation in the basal ganglia and development of Parkinson-like disorders”, explains Sharon Kolk, associate professor in Neurobiology and brain development at Radboud University. Recently researchers are focusing on early-life overexposure to manganese and the potential vulnerability of younger individuals to toxicity also in regard to cognitive and executive functions through the involvement of the frontal cortex.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2020g, July 16). Manganese. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manganese

(2) Manganese - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved July 21, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/25/manganese

Iron is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust. Humans started to master the process of extracting usable metal from iron ores around 2000 BC, although excavations have shown that iron was already being used in old Egypt around 4000 BC, but it took a long time before the use of iron spread and it became (practically and financially) accessible. Copper alloys used in tools and weapons were gradually being replaced by iron. That transition marks the change from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, around 1200 BC. Nowadays, iron alloys such as steel and cast iron are by far the most common industrial metals(1). The large amount of iron in the Earth is thought to contribute to its magnetic field(2).

Iron is required for life because it is a key element in the metabolism of all living organisms. It is an essential component of numerous proteins and enzymes that support essential biological functions, such as oxygen transport, energy production, and DNA synthesis(3). “It is also important for cognitive functioning as it plays an important role in myelination, monoamine synthesis and neuron/glia energy metabolism”, explains Sharon Kolk, associate professor in Neurobiology at Radboud University. Iron deficiency in children has been associated with poor cognitive development, poor school achievement, and abnormal behaviour patterns.

Microbiology researchers at Radboud University are investigating anammox bacteria. These bacteria have a red colour because they contain a large amount of cytochromes; proteins with one or more central iron ions (= an electrically charged atom). Cytochromes perform important conversions in the energy metabolism of the anammox bacteria; they can convert noxious nitrogen into harmless nitrogen gas, which is especially important in the current ‘nitrogen crisis’ (read more about this under element 7: Nitrogen).

Click on "Read more" for information about Iron in research at Radboud University.

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Iron. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron

(2) Iron. (2020, June 5). BYJUS. Retrieved July 18, 2020, from https://byjus.com/chemistry/iron/

(3) Hidgon, J., & Wessling-Resnick, M. (2001). Iron. Linus Pauling Institute. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/minerals/iron

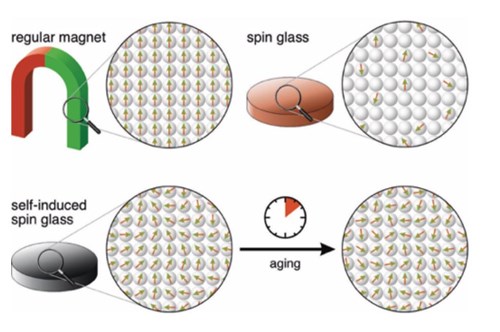

“Iron is the second most abundant element in the Earth’s crust and therefore plays a prominent role in our everyday life. Besides cobalt and nickel, it is one of the three elements, that are ferromagnetic at room temperature. And yet, being widely used in all kind of applications, its magnetic properties are still not fully understood on a fundamental level”, writes Manuel Steinbrecher, post-doc at Scanning Probe Microscopy.

“As a group interested in understanding the transition from microscopic (single atoms) to macroscopic (ensembles of many atoms) magnetism, iron is an appealing element to study. Working in vacuum conditions better than in interstellar space and at temperatures down to -273.1°C (30 milliKelvin above absolute zero temperature) allows us to place single Fe atoms on atomically clean surfaces and study their magnetic properties with astonishing precision. To probe and manipulate a single (iron) atom we use a device called ‘’scanning tunneling microscope’’ (STM). Depending on the substrate of choice (e.g. platinum, copper, magnesium oxide etc), iron’s magnetic properties change due to the interplay of the atom’s with the substrate’s electrons. Furthermore, creating artificial magnetic structures atom-by-atom via atom manipulation allows us to perform experiments in the microscopic as well in the macroscopic regime, on the same platform and with ultimate control. In the future, this will allow a better understanding of fundamental questions in the field of magnetism and might provide opportunities to create atomically precise spintronic devices.”

Cobalt is a brittle, hard, silver-grey transition metal with magnetic properties comparable to those of iron. The element itself was discovered in 1730 by Swedish scientist Georg Brandt. Long before that, cobalt compounds were already used in ancient Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire to colour glass. A necklace with cobalt-coloured blue glass beads from about 2250 BC was found in Persia. Cobalt is still used as drying agents for paints and inks(2).

Compounds of cobalt are also important as oxidation catalysts in a number of industrial processes(1), for example the cobalt carboxylates (known as cobalt soaps). Cobalt is required in small amounts for life and is the only metal found in vitamins (cobalt is the critical component of vitamin B12).

Scientists in the Scanning Probe Microscopy group (SPM) at Radboud University discovered a new mechanism for information storage in the smallest unit of matter: a single atom of cobalt on the surface of black phosphorus. Brian Kiraly and Werner van Weerdenburg (a post-doc and PhD student in the SPM department) discovered that a single cobalt atom on the black phosphorus surface can be in two different states that differ in their orbital configurations (3). Brian Kiraly: “You can imagine the two states as two wells with an energy barrier in between. The atom is stable in its state, unless enough energy is supplied to cross the barrier.” And that’s exactly what he and his colleagues figured out: to flip the state of the atom (0 or 1) back and forth, in a controlled way. And voilà: one single atom can now store information, which can be read out and rewritten. Does this mean that this new technique can be implemented in our smartphones in the next few years? Well, the current experiments were performed at a very low temperature (-269°C), but it does show promise for operation at higher temperatures. The benefit of using the orbital memory is that the energy barrier is higher, compared to magnetic information storage in a single atom, so storage is more robust. A remaining problem is that at room temperature, the atoms can move around on the surface. “You can imagine that it’s not exactly ideal if the bits that you want to read out for information, keep hopping around.”, Werner van Weerdenburg explains. Nonetheless, this research is an important step to denser and more energy-efficient storage of information. And this will have a tremendous impact, when you consider that our computers are currently demanding more than 5 percent of the world’s electricity.

This orbital memory technique, which allows for information storage at the smallest scale, opens up a world of future possibilities. So of course, the researchers didn’t stop there. Implementing the concept of orbital memory utilizing scanning tunneling microscopy, they are now working on research involving atomic neural networks.

Curious? Then the Master’s programme Physics of Molecules and Materials is your best entry. In Alex Khajetoorians’ course “Scanning Probe Microscopy” discusses recent research projects. There is also a possibility to do a Master’s internship at the Institute for Molecules and Materials, in which you will be deeply involved with ongoing research.

Sources

(1) Cobalt. (z.d.). Web Elements. Geraadpleegd 22 juli 2020, van https://www.webelements.com/cobalt/

(2) Hawkins, M. (2001). "Why we need cobalt". Applied Earth Science. 110 (2):

66-71. doi:10.1179/aes.2001.110.2.66

(3) Kiraly, B., Rudenko, A. N., van Weerdenburg, W. M. J., Wegner, D., Katsnelson, M. I., &

Khajetoorians, A. A. (2018). An orbitally derived single-atom magnetic memory. Nature

Communications, 9(1), 3904. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-06337-4

Nickel is silvery white, tough and harder than iron. It is generally known because of its use in coinage(1). Research indicated that nickel was already being used around 3500 BC in several bronze items and to give glass a green colour. Nowadays it is mainly used as pure metal or in the form of alloys for many household and industrial applications, for example to produce stainless steel(2). Nickel slowly oxidises by air at room temperature and is corrosion-resistant. Compounds of nickel are also used to catalyse the hydrogenation of unsaturated fats and oils(1).

The name nickel finds it origins in a 17th-century German tale(3). In the 1600s, German miners searching for copper stumbled upon a previously unknown ore, a pale brownish-red rock. They thought they had discovered another copper ore and attempted to extract the copper – to no avail. The frustrated miners blamed Nickel, a malicious demon in German mythology, and began calling the ore ‘kupfernickel’, which translates to ‘copper demon’. About a century later, in 1751, a Swedish alchemist experimenting with the ore, found that various properties clearly revealed that it wasn’t copper. He extracted nickel and isolated it as a new element; he dropped the ‘kupfer’-part and called the new element nickel.

Sources

(1) nickel | Definition, Properties, Symbol, Uses, & Facts. (z.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 22, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/nickel-chemical-element

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020e, July 12). Nickel. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 22, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nickel

(3) Pedersen, T. (2016, 23 September). Facts About Nickel. Live Science. Retrieved July 22, 2020, from https://www.livescience.com/29327-nickel.html

Copper is, with gold, the oldest known element. It is one of the few elements that can occur in nature in its native metallic form. Researchers discovered copper was already being used 11,000 years ago, then as copper beans, found in northern Iraq. It was the first metal that humans learned to smelt, cast into a shape, and alloy with other metals(1). Copper is key to proper functioning of the immune system (antioxidant activity), blood vessels, nerves (neurotransmitter synthesis, neuronal and glial energy metabolism), and bones.

Olga Luschikova, PhD student Condensed Matter Physics at Radboud University, is studying the role of copper nanoparticles in the production of sustainable fuels. You can learn more about this by watching the video below.

Click on "Read more" to find out about how copper is used in research at Radboud University

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Copper. Wikipedia. Retrieved August 5, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copper

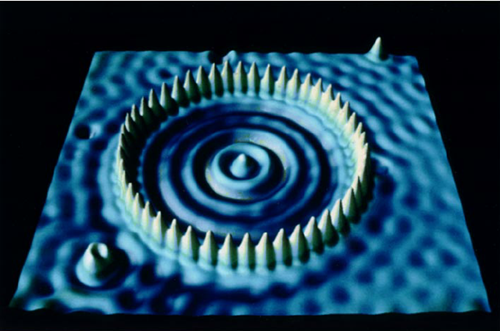

Copper is also being researched at the Scanning Probe Microscopy department (SPM). The scanning tunnelling microscope is a measuring instrument at the Institute for Molecules and Materials, used to examine fundamental physics on the atomic scale. “We are investigating electrons that travel on the surface of copper (to be precise, the Cu(111) surface)”, writes Wouter Jolie, post-doc at the Scanning Probe Microscopy. “Those can be treated as a nearly-free, two-dimensional electron gas, an ideal starting point for our fundamental research. We were able to visualise these "electronic waves" with our scanning tunnelling microscope, as shown by the famous quantum corral experiment. Our focus right now is to artificially pattern the surface of copper with single atoms or molecules to transform these waves into new exotic phases of matter that have been postulated theoretically, but never found in real materials up to date.”

Zinc is the 24th most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, with the largest (workable) lodes in Australia, Asia and the United States. Brass, an alloy of zinc and copper, was used as early as the 3rd millennium BC. Although evidence shows that zinc production sites date back to the 6th century BC, it wasn’t produced on a large scale until the 12th century, in India (1). Now, the element is mainly used in corrosion-resistant zinc plating of iron. Other applications include batteries or castings, and compounds of zinc can be found in dietary supplements, deodorants, shampoos and paint. Zinc is a micronutrient; a mineral essential to organisms, including humans.

Researchers at Radboudumc have discovered how zinc inhibits the development of macular degeneration (AMD); an age-related eye disease that gets worse over time. Small abnormalities in the genes of the complement system cause a slight over activity of the complement system - an important part of the immune system, which leads to an accelerated wear of the yellow spot (macula) of the eye. Zinc "calms" that system, inhibiting the development of old-age blindness (2). This discovery could have far-reaching consequences for a variety of other conditions, in which the complement system also plays a role.

Sources:

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Zinc. Wikipedia. Retrieved 2 February 2021, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zinc

(2) Smailhodzic, D., van Asten, F., Blom, A. M., Mohlin, F. C., den Hollander, A. I., van de Ven, J. P. H.,

van Huet, R. A. C., Groenewoud, J. M. M., Tian, Y., Berendschot, T. T. J. M., Lechanteur, Y.

T.E., Fauser, S., de Bruijn, C., Daha, M. R., van der Wilt, G. J., Hoyng, C. B., & Klevering, B. J.

(2014). Zinc Supplementation Inhibits Complement Activation in Age-Related Macular

Degeneration. PLoS ONE, 9(11), e112682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0112682

Gallium is a soft, silver-white metal that is a brittle solid at a lower temperature. Gallium does not occur as a free element in nature, but compounds of gallium are found in zinc ores and bauxite. Because gallium is a soft metal which melts quite easily (it will melt in your hand due to your body temperature), gallium is mainly used as an alloying element to make alloys that melt at low temperatures (1). It is also used as a semiconductor in electronics.

When gallium solidifies, it can expand up to 3.1% in volume. Storage in glass or metal containers should therefore be avoided; if the temperature were to drop, the container would rupture upon solidification. If too much force is applied, gallium may fracture conchoidally (smooth, curved surfaces, without any natural planes of separation) (2).

Sources:

(1) Gallium: Het element. (2016, November 30). InfoNu.

https://wetenschap.infonu.nl/scheikunde/154971-gallium-het-element.html

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2021, January 21). Gallium. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gallium

Because it rarely appears in high concentration, germanium was discovered comparatively late in the history of chemistry. In 1869, founder of the periodic table, Dmitri Mendeleev already predicted its existence and some of its properties from its position on his periodic table, and called the element ekasilicon (1). It was German chemist Clemens Winkler who found the new element nearly two decades later, in 1886, along with silver and sulfur. Winkler named the element after his country, Germany. The main application of germanium today is as a carrier material for LEDs, laser diodes and solar cells. You can also find it in infrared optics. Germanium oxide exhibits the unusual property of having a high refractive index for visible light, but transparency to infrared light. This is why it is used a lot in infrared optics (2), wide-angle camera lenses and objective lenses for microscopes (3).

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2020t, December 2). Germanium. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Germanium

(2) Periodiek systeem - informatie over alle elementen - VNCI. (n.d.-c). C3 Centrum

JongerenCommunicatie Chemie. Retrieved 4 February 2021, from

https://periodieksysteem.com/element/germanium

(3) Germanium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal

Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 4 February 2021, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic

table/element/32/germanium

Arsenic is a metalloid and occurs in many minerals, usually in combination with sulfur and metals, but also as a pure elemental crystal. (1) Arsenic and its compounds are used in the production of pesticides, treated wood products, herbicides, and insecticides. However, these applications are declining with the increasing recognition of the toxicity of arsenic. Its toxicity is not a new finding; humans have known for hundreds, if not thousands of years that arsenic is poisonous. From the time of the Roman Empire all the way to the Victorian era, arsenic was considered the "king of poisons" as well as the "poison of kings." (2) The name is thought to come from 'arsenikon', the Greek name for the yellow pigment orpiment. (3) The word is also related to the Greek word "arsenikos," meaning "masculine" or "potent.".

Arsenic is a naturally occurring element in the Earth's crust (20th most abundant) and is present at high levels in the groundwater of several countries. However, due to its toxicity, arsenic-contaminated water used for drinking, food preparation and irrigation threatens the health of millions of people worldwide. Within a few years of exposure to arsenic-contaminated water, arsenical skin lesions appear, often leading to skin cancer. This is an especially concerning health problem in populations living along river floodplains of South and Southeast Asia that rely on shallow groundwater wells for drinking water and irrigation, which has resulted in the so-called “worst mass poisoning of human population in history”. (4) Researchers at Radboud University have identified a methane-mediated mechanism for arsenic mobilization. They found that “methane functions as an electron donor for methanotrophs, triggering the reductive dissolution of arsenic-bearing iron(III) minerals, increasing the abundance of genes related to methane oxidation, and ultimately mobilizing arsenic into the water.” (5) As methane has a common presence in arsenic-contaminated aquifers, the researchers suggest that this “methane-driven arsenic mobilization may contribute to arsenic contamination of groundwater on a global scale.” (5)

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2021c, January 28). Arsenic. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arsenic

(2) Pedersen, T. (2016, July 28). Facts About Arsenic. Livescience.Com.

https://www.livescience.com/29522-arsenic.html

(3) Arsenic - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society

of Chemistry. Retrieved 4 February 2021, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic

table/element/33/arsenic

(4) Smith, A. H., Lingas, E. O. & Rahman, M. Contamination of drinking-water

by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency. Bull. World Health

Organ. 78, 1093–1103 (2000).

(5) Glodowska, M., Stopelli, E., Schneider, M. et al. Arsenic mobilization by anaerobic iron-

dependent methane oxidation. Commun Earth Environ 1, 42 (2020).

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-020-00037-y

Selenium was discovered by chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius in Stockholm in 1817. He had shares in a sulfuric acid works and was interested in the red-brown sediment which collected at the bottom of the chambers. The element is a semi-metal that can exist in two forms: as a silvery metal or as a red powder. (1) It is named after Selene, the Greek goddess of the moon, because the element was found together with tellurium, named after the Latin ‘tellus’, meaning Earth. (2) Selenium has photovoltaic properties, which convert light directly into electricity. In addition, selenium is also photoconductive; under the influence of light, the electrical conductivity increases. It is therefore useful in photocells, solar cells and photocopiers.

Selenium is an essential trace element for humans. Our bodies contain about 14 milligrams. Too little selenium can cause health problems, but too much is also dangerous. Researchers at Radboudumc found that selenium may play a role in whether or not prostate cancer will spread. Their analysis showed that selenium changes the activity of certain genes implicated in the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in the prostate, a process linked to cancer progression. Selenium seems to have an inhibitory effect on this EMT process. (3)

Sources

(1) Selenium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). Royal Society

of Chemistry. Retrieved 4 February 2021, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic

table/element/34/selenium

(2) Wikipedia-bijdragers. (2021, January 20). Seleen. Wikipedia.

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seleen

(3) Kok, D. E. G., Kiemeney, L. A. L. M., Verhaegh, G. W., Schalken, J. A., van Lin, E. N. J. T., Sedelaar, J.

P. M., Witjes, J. A., Hulsbergen - van de Kaa, C. A., van ’t Veer, P., Kampman, E., & Afman, L.

A. (2017). A short-term intervention with selenium affects expression of genes implicated in

the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the prostate. Oncotarget, 8(6), 10565–10579.

https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14551

Bromine is one of the few elements which is liquid at standard temperature and pressure (STP). Elemental bromine is very reactive and thus does not occur free in nature, but in salts similar to table salt. Its name was derived from the Ancient Greek βρῶμος, meaning "stench", referring to its sharp and unpleasant smell. At high temperatures, organobromine compounds (organic compounds that contain carbon bonded to bromine) easily dissociate to yield free bromine atoms, a process that stops free radical chemical chain reactions. This effect makes organobromine compounds useful as fire retardants, which is how more than half the bromine produced worldwide is used. The same ability causes volatile organobromine compounds to dissociate under ultraviolet sunlight, which releases free bromine atoms in the atmosphere, causing ozone depletion. (1) As a result, many organobromide compounds are no longer used.

Researchers at Radboud University have used bromine to produce graphene, a material which consists of a single layer of carbon atoms (learn more about graphene under ‘Carbon’). The researchers produced suspensions of graphene sheets by combining solution-based bromine intercalation and mild sonochemical exfoliation. (2)

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2021d, February 2). Bromine. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bromine

(2) Widenkvist, E., Boukhvalov, D. W., Rubino, S., Akhtar, S., Lu, J., Quinlan, R. A., Katsnelson,

M. I., Leifer, K., Grennberg, H., & Jansson, U. (2009). Mild sonochemical exfoliation of

bromine-intercalated graphite: a new route towards graphene. Journal of Physics D:

Applied Physics, 42(11), 112003. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/42/11/112003

Krypton is a colourless, odourless and tasteless noble gas, which is why its name comes from the Ancient Greek: κρυπτός, Romanized: kryptos, meaning ‘hidden’. Like other noble gases, krypton is used in lighting and photography. Krypton light has many spectral lines, and krypton plasma is useful in bright, high-powered gas lasers, each of which resonates and amplifies a single spectral line. From 1960 to 1983, the official length of a meter was defined by the 606-nanometer wavelength of the orange spectral line of krypton-86. (1) Although krypton is rare and inert, it appears to be able to form connections with a few other elements. Oxygen isn't one of them – the mythical ‘kryptonite’ only exists in Superman stories. (2)

Sources

(1) Wikipedia contributors. (2021a, January 11). Krypton. Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Krypton

(2) Periodiek systeem - informatie over alle elementen - VNCI. (n.d.-d). C3 Centrum

JongerenCommunicatie Chemie. Retrieved 4 February 2021, from

https://periodieksysteem.com/element/krypton

It seems fair to call rubidium hard to handle: it ignites spontaneously in air and reacts violently with water. In nature, it is only found as an impurity in other minerals. Commercial usage is limited due to its high price and limited supply(1). But wait: it does get better. Rubidium’s name comes from the Latin word ‘rubidus’, which refers to the deep red colour of its emission spectrum. This quality is sometimes exploited in fireworks, resulting in a purple blast(2). Furthermore, rubidium can be used in atomic clocks and it has isotopes that can locate brain tumours(3). Rubidium is also useful when dating – not people, but rocks. This method, rubidium–strontium dating, has been used extensively to determine the age of lunar rocks and meteorites. It builds on the bizarre half-life of one of rubidium’s natural isotopes. Given some quantity of this isotope, it would take 49 billion years before only half is left due to radioactive decay. That is three times as long as the estimated age of the universe(4)!

Sources

(1) Rubidium | chemical element. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://www.britannica.com/science/rubidium

(2) Wikipedia contributors. (2020c, July 24). Rubidium. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubidium

(3) Rubidium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table. (n.d.). www.rsc.org. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://www.rsc.org/periodic-table/element/37/rubidium

(4) Wikipedia contributors. (2020a, June 6). Rubidium–strontium dating. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubidium%E2%80%93strontium_dating